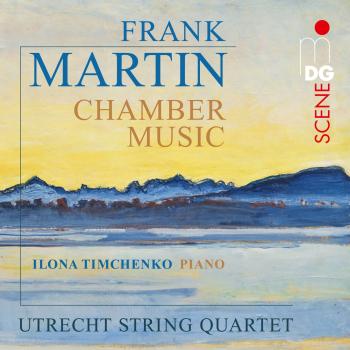

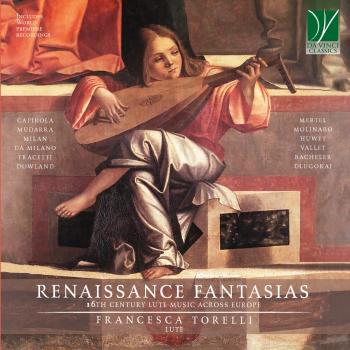

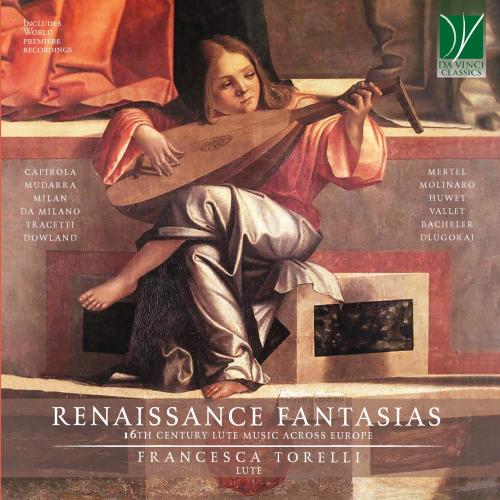

Renaissance Fantasias: 16th Century Lute Music across Europe Francesca Torelli

Album info

Album-Release:

2022

HRA-Release:

15.11.2024

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Subgenre: Instrumental

Artist: Francesca Torelli

Composer: Vincenzo Capirola (1474-1548), Alonso Mudarra (1510-1580), Luys Milán (1500-1560), Lorenzino Tracetti (1552-1590), John Dowland (1562-1626), Simone Molinaro (1565-1615), Albert Dlugoraj (1558-1618)

Album including Album cover

- Vincenzo Capirola (1474 - 1548): Ricercare quinto:

- 1 Capirola: Ricercare quinto 05:07

- Alonso Mudarra (1510 - 1580): Fantasia que contrahaze la harpa:

- 2 Mudarra: Fantasia que contrahaze la harpa 02:26

- Luis Milán (ca. 1500 - 1561): Fantasias X-XI:

- 3 Milán: Fantasias X-XI 04:53

- Francesco da Milano (1497 - 1543): Fantasie N 81- 84 - 40:

- 4 Milano: Fantasie N 81- 84 - 40 04:17

- Fantasia divina:

- 5 Milano: Fantasia divina 05:23

- Fantasia 51:

- 6 Milano: Fantasia 51 03:02

- Lorenzo Tracetti (1552 - 1590): Due Fantasie:

- 7 Tracetti: Due Fantasie 03:15

- John Dowland (1563 - 1626): Fantasia P5:

- 8 Dowland: Fantasia P5 02:37

- Elias Mertel (1561 - 1626): Phantasia 25:

- 9 Mertel: Phantasia 25 01:39

- Simone Molinaro (1565 - 1636): Fantasia V:

- 10 Molinaro: Fantasia V 03:51

- Gregory Huwet (1550 - 1617): Fantasia:

- 11 Huwet: Fantasia 04:40

- Nicolas Vallet (1583 - 1642): La Mendiante Fantasye:

- 12 Vallet: La Mendiante Fantasye 04:13

- Elias Mertel: Preludium 197-Phantasia 108:

- 13 Mertel: Preludium 197-Phantasia 108 04:14

- John Dowland: Fantasia P1:

- 14 Dowland: Fantasia P1 04:50

- Daniel Bacheler (1572 - 1619): Prelude-Fantaisie:

- 15 Bacheler: Prelude-Fantaisie 06:18

- Albert Dlugoraj (1557 - 1619): Finale:

- 16 Dlugoraj: Finale 02:00

- John Dowland: A Fancy P7:

- 17 Dowland: A Fancy P7 05:05

Info for Renaissance Fantasias: 16th Century Lute Music across Europe

The roots of the lute dig deep into antiquity. Depending on how one defines a lute, its ancestors can be dated back to approximately 5,000 years ago. This exceptional age led to the development of numerous variants of this instrument, found in Europe and in the Middle East, with common traits and distinctive features. In spite of this, the fortunes of the Western lute have not been constant. It is abundantly documented in the medieval period, but with structural features, performing techniques and purposes markedly different from those it would assume later. It was indeed in the Renaissance that the lute knew its golden age. One might even say that it was the most important instrument in the Renaissance era, particularly as concerns solo performance. In fact, the versatility of this instrument – capable of playing melodies, polyphony, and harmony – not only qualified it as the most beloved instrument of the time, but also encouraged and prompted the composition of many works, as well as the very evolution of the musical language, styles, and forms of the era.

It was an instrument which could perfectly accompany other sound mediums, such as the voice or other instruments, but which could also sustain the complexity of a polyphonic texture without strain. Unavoidably, therefore, on the one hand it derived its earliest repertoire directly from transcriptions of vocal music, but, on the other, it developed its own solo repertoire primarily out of the practice of improvisation. This represented its greatest fortune, but also, alas, our misfortune, since improvised music is only occasionally written down: thus, countless improvisations are lost forever, and even the written sources that have been preserved are silent on many aspects of performance practice. Notwithstanding this, what we do have is more than enough for savouring the beauty, richness, fantasy and creativity of this repertoire, along with the distinctive national and local features of the lute idiom in Europe. This Da Vinci Classics album leads us through this fascinating itinerary, where Renaissance internationalism encounters localisms, and where improvisation and improvised practices intertwine with the precious testimony of the written pages.

For a long time, I wished to realise an album collecting some of the best compositional expressions of the Renaissance lutenists.

The Fantasia is the musical genre which, in my opinion, best represents the Renaissance composer-lutenist. Sixteenth-century composers dedicated themselves mightily also to dance forms, but, in dances, their task was mainly that of writing diminutions/variations. In fact, in many cases dances pre-existed, at least in their basic form, as popular pieces. Composers elaborated enriched versions of them, making them suitable for court entertainment. Renaissance lutenists also intabulated of many vocal works, but, in this case, it is still more evident that the music does not belong entirely to them, but first and foremost to the composers who wrote the original polyphonic vocal pieces. Lutenists-composers frequently limited themselves to the addition of sober (or even abundant) diminutions, with very varied results.

The forms in which the composer’s personality is best expressed are therefore the so-called free forms. In the Renaissance, these are identified mainly with the Fantasia and the Ricercare (actually these two are synonyms, in the period under observation), as well as the Prelude, which was found also in the first French musical prints.

In the international recording panorama, I believe that no recording has hitherto appeared collecting an anthology of lute fantasias spanning over the entire timeframe of the musical Renaissance (from the early sixteenth century to the early seventeenth century), and coming from all over Europe. The European countries where there was as flowering of lute music in the Renaissance were primarily Italy, France, Germany, Spain, England, the Netherlands, and Poland. The most beautiful Renaissance Fantasias travelled, at that time, throughout Europe, both in printed volumes, and in manuscript form. By the end of the Renaissance some composers, among whom Robert Dowland and Jean-Baptiste Besard, felt the need to produce bulky collections containing the European “greatest hits” for the lute.

For my own recorded collection, I chose works by very famous composers, such as Dowland or Francesco da Milano, but also others by lesser-known composers, such as Tracetti or Mertel, when their music seemed to have brought innovative elements, and, at the same time, when it seems capable of communicating something to our own times.

Vincenzo Capirola’s Ricercare Quinto, which I chose as the opening piece of the album, is found in a manuscript written about 1510-20, i.e. one of the earliest sources of lute music. It is therefore surprising to find that this is a long and complex piece, made of several sections, and exploring the lute’s fingerboard’s entire range: this bears witness to an art which was already mature, and not just moving its first steps.

Within this collection, Alonso Mudarra’s Fantasia que contrahaze la harpa is the one I feel as the most “modern”, probably due to the almost obsessive insistence on which it is built, and which, in the second part, becomes coloured with dissonances. This insistence does not last for long, but one would like it to last forever. It is like the first seed of a way of composing which would reach its full development only several centuries later.

Two pieces, i.e. Luis Milan’s Fantasias X and XI, are excerpted from a printed volume of music for the vihuela, the Spanish stringed instrument tuned in the same way as the lute. In this volume we find the first description ever of “rubato” performance: this interpretive process is, in my opinion, essential for performing the Fantasias written in those years.

There are many fascinating and well-built Fantasias by Francesco da Milano. I firstly chose three of them (nos. 81, 84, and 40), which are extremely short: in spite of their synthesis, they transmit, in my view, an exemplary sense of fulfilment.

Francesco da Milano’s Fantasia divina is found in two manuscript copies 1, but in both the text is laid with errors and inconsistencies. I used both sources in order to elaborate my own version. This is one of Francesco’s longest Fantasias, with many and varied sections, which are however marked by his stylistic imprint.

I believe that Francesco’s Fantasia 51 fascinates the listener for its structural asymmetries, and also for a certain sense of “unresolvedness” which comes from the motifs which are presented but later not continued in the various voices. It had for me an irresistible attractive power, particularly in the bass’ enthralling melody found in the piece’s second part.

Lorenzino Tracetti’s Two Fantasias are the pieces which stylistically best anticipate the Toccata, i.e. the favourite “free form” in Italy in later years. In particular, the first of them, recorded here in world premiere, is written in an improvisational style, and conceived as a melody sustained by a bass, rather than as the superimposition of several melodic lines in counterpoint.

The Genoese lutenist Simone Molinaro was also an organist; perhaps precisely for this reason, his lute works have a density of texture which is hardly found in the works by other coeval lutenist-composers. His Fantasia V is a paradigm of the rationality and refinedness of a musical thought expressed on the lute.

The French-Dutch lutenist Nicolas Vallet’s La Mendiante Fantasye is woven around a chromatic motif. In its first part, this chromaticism is found even in two voices at the same time, producing unusual harmonies. Then it becomes rarefied; it dissolves toward the end, leaving room for an ending with serene arpeggiated chords.

In spite of the recent studies by Wirth and Robinson 2, the lute output of Dutchman Gregorius Huwet is still surrounded by mystery. Huwet worked as a lutenist at the Wolfenbüttel court, where, in 1594, he met John Dowland: with him, he travelled to the court of Kassel in the following year. The musical exchanges between Huwet and his better-known colleague must have been more significant than those we now know. In fact, several pieces by Huwet contain quotes from Dowland’s works, but state-of-the-art research cannot yet clarify their mutual musical influences. This Fantasia by Huwet contains a chromatic motif found throughout the piece. Its insistence, united with a construction implying a long, static wait before the unfolding of a liberating concluding section, is what turns this work into a little masterpiece.

German lutenist Elias Mertel authored one of the conspicuous European anthologies at the end of the Renaissance, i.e. his Hortus Musicalis Novus of 1615. Unfortunately, the pieces’ individual composers are not mentioned in the collection. The Preludio and the two Fantasie thus could have been composed by Mertel himself or by others, and are recorded here in world premiere.

Even though he was a famous lutenist at his time, Daniel Bacheler did not publish lute music. Some fifty-odd of his works for the lute have been preserved in manuscript sources by other English composers. I combined his dark and profound Preludio in C minor with his only know Fantasia.

The Finale by the Polish composer Dlugoraj, in spite of this title found in a manuscript, is catalogued as a prelude in Hortus Musicalis Novus. Its simple and tranquil character seemed to constitute an effective contrast with the dramatic character of Bacheler’s preceding pieces.

I have still said nothing about the Fantasias by John Dowland I added to the collection. Much has been written about John Dowland, his life and music – including questions, his successes and failures, the attributions… – but I find it difficult to write about his Fantasias. I am tempted to let his music simply speak. I only add that I chose these three Fantasias because, in my opinion, in its concluding section each one has an opening, a change in register, whereby musical scoring becomes capable of freeing itself from the stereotypes of counterpoint, and, therefore, from the language of his time.

This music becomes capable of making a journey involving more than space (through the Europe of his time), and capable of travelling also in time, toward us. It is capable not just of evoking, but also, simply, to touch us.

Francesca Torelli, lute

Francesca Torelli

is considered among the best Italian interpreters of lute music of her generation.

After earning a degree in lute with the highest marks at the Conservatory of Verona under the guidance of Orlando Cristoforetti, Francesca Torelli completed her studies with Nigel North at the Guildhall School of Music in London. At the same time, she studied renaissance and baroque singing with Auriol Kimber.

From the beginning, her concert activities have featured the repertoires for voice and lute (singing while accompanying herself on the instrument), as well as the solo repertoire for lute and theorbo and basso continuo. Since 2000 she also has performed as a director of early music ensembles.

As a soloist, she has participated in numerous festivals in Europe, South America and Australia.

She has provided and played the music for various theatrical productions and has appeared as a lutenist on television programs for RAI 2, Channel 4, and others.

Francesca has recorded for the labels Tactus, Dynamic, Stradivarius, Mondo Musica and Nuova Era, with the ensembles Cappella Artemisia, Sans souci, Cappella Palatina, Accademia Farnese and the chamber orchestra Offerta Musicale of Venice. She has also recorded for the national Italian radio RAI Radiotre, WDR and other European radio and television networks.

She has also collaborated with the orchestra of the Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, the Vivaldi ensemble of the Solisti Veneti, Il Ruggiero, Accademia degli Astrusi, Capella Regiensis.

Francesca has made two solo recordings (on Tactus) with music by Pietro Paolo Melli and Alessandro Piccinini (reprint Brilliant 2011) and the albums John Dowland: Lute songs, lute music (2010) , Musique pour le Roy-Soleil: Robert de Visée works for theorbo (2013), Italian Baroque Music for Archlute (2017), Le Dialogue: Charles Mouton Lute suites (2021) for Magnatune. All this recordings received great appreciation from the press.

In 2006 A tutor for the Theorbo, an handbook written by Francesca Torelli went out for Ut Orpheus editions. This is the first and only method published in the world dedicate to this instrument.

She is the founder and director of the ensemble Scintille di musica with whom she has recorded six CD for the Futuro antico series on EMI and Lungomare, featuring the voice of Angelo Branduardi. These recordings are about Sixteenth and Seventeenth century Italian music: Mantova, la musica alla corte dei Gonzaga; Venezia e il Carnevale; Musica della Serenissima; Roma e la festa di San Giovanni; Il Carnevale romano; Musica alla corte dei Principi-Vescovi.

Francesca has directed the Milano Conservatorio’s early music ensemble Andromeda in performances of Baroque oratorios (Kapsberger, de Rossi, Carissimi) theatrical works (Purcell) and concerts productions.

She has taught lute at the conservatories of Bari and Vicenza and has held seminars and master classes at numerous Universities and musical institutions.

Since 2001 she is lute professor at the “GiuseppeVerdi” Conservatory in Milan, where she is currently also director of the Early Music Institute.

This album contains no booklet.