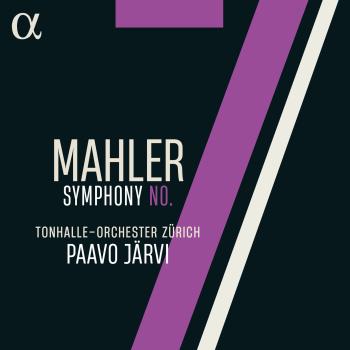

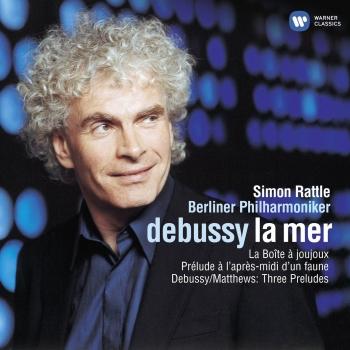

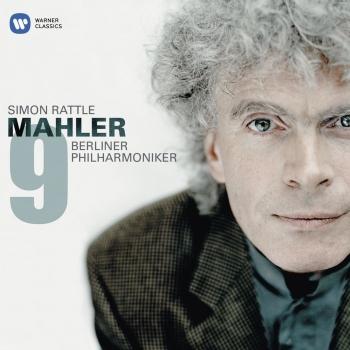

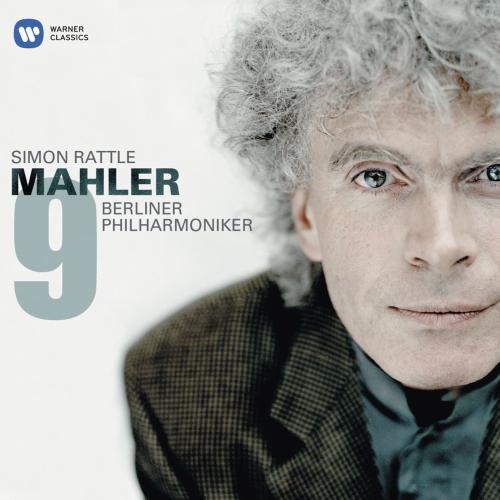

Mahler: Symphony No. 9 Berliner Philharmoniker & Sir Simon Rattle

Album info

Album-Release:

2008

HRA-Release:

09.05.2014

Album including Album cover Booklet (PDF)

I`m sorry!

Dear HIGHRESAUDIO Visitor,

due to territorial constraints and also different releases dates in each country you currently can`t purchase this album. We are updating our release dates twice a week. So, please feel free to check from time-to-time, if the album is available for your country.

We suggest, that you bookmark the album and use our Short List function.

Thank you for your understanding and patience.

Yours sincerely, HIGHRESAUDIO

- 1 I. Andante comodo 28:57

- 2 II. Im Tempo eines gemächlichen Ländlers. Etwas täppisch und sehr derb 15:57

- 3 III. Rondo-Burleske (Allegro assai. Sehr trotzig) 12:38

- 4 IV. Adagio (Sehr langsam und noch zurückhaltend) 26:02

Info for Mahler: Symphony No. 9

Simon Rattle began recording the Mahler symphonies for EMI Classics in 1987, the first foray being Symphony No. 2 with the CBSO, and the subsequent cycle has seen great critical success.

Gramophone said of Sir Simon’s earlier recording of Mahler 9 with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra for EMI: “How thrilling it is to hear the score projected at white heat! This is at various times the loudest, softest, fastest and slowest Mahler Ninth on disc.” And the magazine commented on his Mahler 10 recording with the BPO, which was his first Mahler with the orchestra: “Rattle makes the strongest possible case for an astonishing piece of revivification that only the most die-hard purists will resist. Strongly recommended.”

“Rattle and the Berliners are capable of taking one's breath away. It's in the final Adagio that Rattle and his orchestra make the most powerful impact. The strings sound gorgeous, of course, yet there's grit as well as radiance in their tone. And it's only in the final pages that the earthy impurities are leeched, leaving a breath-like purity that ebbs into rapt silence.” (Gramophone Magazine)

“In his previous recording of Mahler's Ninth Symphony, made live with the Vienna Philharmonic in 1993, Simon Rattle tapped into the music's emotional extremes to produce a surprisingly volatile reading full of precipitous accelerandi and wrenching ritardandi. There's some of that volatility in this new account from Berlin, too, though it's certainly less pronounced.

There are places, too, where more tenderness wouldn't come amiss: the entrance of the solo violin in the first movement's recapitulation is so much sweeter in Vienna. But Rattle and the Berliners are also capable of taking one's breath away. Listen later in the same movement, as they gather the seemingly chaotic tangle of melodic filaments together, creating a single, gigantic, darkly radiant chord.

The rustic dances in the second movement have a strong, rough-hewn quality, even if they sound slightly dour when compared with the more gemütlich charm of, say, Abbado's Berlin recording. Rattle doesn't push hard in the Rondo-Burleske until the end; instead, he aims for clarity and articulateness, and scrupulously observes all the dynamic twists and turns. It's an effective approach, though less adrenalin-pumping than Karajan.

It's in the final Adagio, however, that Rattle and his orchestra make the most powerful impact. The strings sound gorgeous, of course, yet there's grit as well as radiance in their tone.

And it's only in the final pages that the earthy impurities are leeched, leaving a breath-like purity that ebbs into rapt silence.” (Gramophone Classical Music Guide)

Berliner Philharmoniker

Sir Simon Rattle, conductor

Berliner Philharmoniker

Beginnings

Spring 1882: When Benjamin Bilse announces the intention of taking his already underpaid orchestra on the train to Warsaw in fourth class for a concert, that's the last straw for 54 of his musicians. Calling themselves the 'former Bilse Kapelle', they decide to declare their independence. But at first the young ensemble has economic problems of its own to confront, and it isn't until the Berlin concert agent Hermann Wolff takes over its organization in 1887 that a stable basis for the future is finally established. He changes the name to 'Berliner Philharmonisches Orchester', turns a renovated roller-skating rink into the first 'Philharmonie' and seeks out the best conductors of the day for his musicians.

The great orchestral trainers

Hans von Bülow has already formed a first-class ensemble from his Meiningen Court Orchestra when he takes over the Berliner Philharmoniker. In only five years at the helm he lays the foundation of those special musical qualities that from now on will be indissolubly linked with the orchestra's name. Bülow's successors, on the other hand, come to stay. Arthur Nikisch, who takes up his post in 1895, goes on to influence the orchestra's style decisively for the next 27 years. He once writes: 'It can be asserted without hesitation that in a first-rate orchestral body every member deserves to be described as an 'artist',' and with this creed he encourages the Berlin musicians to develop a sense of themselves as 'soloists'. That quality still represents one of the Philharmonic's unmistakable trademarks.

When Nikisch dies in 1922, the orchestra unanimously chooses Wilhelm Furtwängler to succeed him. The young conductor builds on Nikisch's achievements. His idiosyncratic beat and his impassioned, inspired music-making demand from the musicians an extremely high level of autonomy and sensitivity. Furtwängler's philosophy emphasizes the timelessness of great works of art, and thus his greatest affinity is for the Classical and Romantic masters. He and his Berlin orchestra become legendary interpreters of the works of Beethoven, Brahms and Bruckner. At the same time Furtwängler expands the repertoire to include contemporary pieces by Schoenberg, Hindemith, Prokofiev and Stravinsky.

The turmoil of war

The National Socialist dictatorship and the war do irreparable damage to the German cultural landscape – including the Berliner Philharmoniker. The regime’s maniacal racial policy leads to the loss of valuable musicians, and the orchestra finds itself isolated from the international exchange of soloists and conductors. Meanwhile there is also an attempt to turn Germany’s representative ensemble into an instrument of official cultural politics. Nevertheless Furtwängler and the orchestra manage to salvage its artistic substance through the war.

But the comparatively rapid turnover of conductors in the early post-war period speaks for itself. The Philharmonic under Leo Borchard already gives its first concert on 26 May 1945 in the Titania-Palast, a converted cinema, but in August, through a tragic mistake, Borchard is shot and killed by an occupying soldier. Chosen to succeed him is a completely unknown young Romanian, virtually straight out of the Berlin Music Hochschule, where he has been studying. But the orchestra’s judgment proves itself to be acute: Sergiu Celibidache arouses great enthusiasm with his vivid personality and widely varied programmes until 1952, when the orchestra’s leadership is officially returned to the hands of Furtwängler. Also coming in the postwar period is the founding in 1949 of the “Gesellschaft der Freunde der Berliner Philharmonie e.V. ” (Society of Friends of the Berliner Philharmonie Inc.), which in subsequent decades sponsors the building of the new Philharmonie and continues to provide the hall with financial support.

The Karajan era

In November 1954 Wilhelm Furtwängler dies. The following April the Berliner Philharmoniker chooses as its artistic director the man who is to remain with the ensemble longer than any other - Herbert von Karajan. He works with the orchestra to cultivate a specific sound, an unprecedented perfection and virtuosity which lay the groundwork for the ensemble's national and international triumphs - both in the concert hall and through countless recordings.

Moreover, Karajan is able to expand the orchestra's activities in a number of new directions. With the founding of the Salzburg Easter Festival in 1967 the orchestra now has its own major international festival and an opportunity to make its mark as an opera orchestra. A further initiative is the Orchestra Academy of the Berliner Philharmoniker (Orchester-Akademie der Berliner Philharmoniker), in which young and talented instrumentalists are trained through practical experience to meet the stringent demands of a top-flight orchestra. The construction of the new Philharmonie also takes place during the Karajan era. Since October 1963 the orchestra has made its home in the concert hall designed by Hans Scharoun, (to which a chamber music hall is added in 1987).

Claudio Abbado

Herbert von Karajan died in July 1989, after nearly 35 years as the orchestra's artistic director. His successor was a familiar face. Claudio Abbado conducted the Philharmoniker for the first time in 1966 and earned the musicians' highest esteem during the intervening years. He was not an orchestral trainer in the manner of his predecessors but led through the sheer force of his conviction and artistic presence.

Abbado's programmes brought a pronounced shift in emphasis. Each cycle of concerts was given a thematic focus – for example, 'Faust', 'The Wanderer' or 'Music is Fun for All'. This conceptual modernisation corresponded to a significant rejuvenation of the Philharmoniker themselves. Well over half of the current membership joined the orchestra during this time. In February 1998 Claudio Abbado announced that he would not renew his contract beyond the 2001/2002 season, and in June of the following year the Berliner Philharmoniker elected a new chief conductor by a wide majority.

Sir Simon Rattle

With Sir Simon Rattle's appointment, the orchestra not only succeeded in recruiting one of the most talented conductors of the younger generation but also in introducing a series of important innovations. The conversion of the orchestra into a public foundation, the Stiftung Berliner Philharmoniker, on 1 January 2002 has provided a modern structure which allows a broad range of opportunities for creative development while ensuring the ensemble's economic viability. The foundation enjoys the generous support of the Deutsche Bank, its principal sponsor. One focus of this sponsorship is the education programme established when Sir Simon Rattle assumed his post and through which the orchestra addresses a broad public – young people in particular. Sir Simon Rattle has summarised his intentions as follows: 'The education programme reminds us that music is no mere luxury, but instead a fundamental need. Music must be a vital and essential element in the life of each individual.' In the 130-year history of the Berliner Philharmoniker this represents an expansion of the orchestra's cultural mandate, one to which they are dedicating themselves with characteristic commitment.

For this commitment the Berliner Philharmoniker and their artistic director were appointed as international UNICEF Ambassadors, an honour conferred for the first time on an artistic ensemble. In June 2011 the Berliner Philharmoniker and Sir Simon Rattle received the Glashütte Original Music Festival Award for their educational programming and their role as a model for the programmes of other cultural institutions.

As a result of the Berliner Philharmoniker Foundation's desire to open up the Philharmonie to wider sections of the population and make it an attractive location during the day as well, two new concert formats were launched during the 2007/2008 season. During the free Lunchtime Concerts presented every Tuesday in the Foyer of the Philharmonie, outstanding chamber music works are performed by ensembles from the Berliner Philharmoniker, the city's universities and other Berlin orchestras. In the chamber music series Alla turca, artists from the Orient and Occident came together for cultural dialogue and introduced their music, exploring the historical and cultural differences of the two cultures. Beginning with the 2011/2012 season, Alla turca was expanded to Unterwegs (Underway), a new world music series developed and presented by Roger Willemsen. Together with their partner, the Deutsche Bank, the Berliner Philharmoniker initiated a forward-looking project in January 2009: the Digital Concert Hall. Concerts by the Berliner Philharmoniker can now be enjoyed live in the Internet and retrieved from the video archive of the Digital Concert Hall at any time.

In spring of 2012 the Berliner Philharmoniker appeared for the last time at the Salzburg Easter Festival. In 2013 the orchestra will launch its new Easter Festival in Baden-Baden, with four opera performances each year, symphonic concerts and a wide array of chamber music programmes. In addition, the orchestra will also devote itself particularly to encouraging young musicians and artists.

Booklet for Mahler: Symphony No. 9