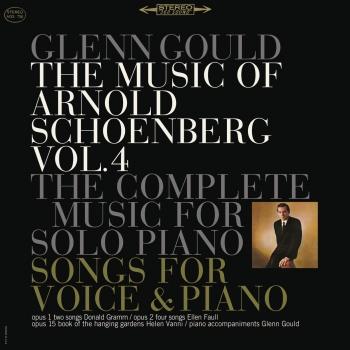

The Music of Arnold Schönberg: Songs and Works for Piano Solo (Remastered) Glenn Gould

Album info

Album-Release:

2015

HRA-Release:

09.09.2015

Label: Sony Classical

Genre: Classical

Subgenre: Instrumental

Artist: Glenn Gould

Composer: Arnold Schönberg (1874–1951)

Album including Album cover Booklet (PDF)

I`m sorry!

Dear HIGHRESAUDIO Visitor,

due to territorial constraints and also different releases dates in each country you currently can`t purchase this album. We are updating our release dates twice a week. So, please feel free to check from time-to-time, if the album is available for your country.

We suggest, that you bookmark the album and use our Short List function.

Thank you for your understanding and patience.

Yours sincerely, HIGHRESAUDIO

- Arnold Schoenberg (1874–1951): Zwei Gesänge, Op. 1

- 1 I. Dank 06:01

- 2 II. Abschied 08:42

- Vier Lieder, Op. 2

- 3 I. Erwartung 04:15

- 4 II. Schenk mir deinen goldenen Kamm 03:43

- 5 III. Erhebung 01:11

- 6 IV. Waldsonne 02:46

- Das Buch der hängenden Gärten, Op. 15

- 7 I. Unterm Schutz von dichten Blättergründen 02:37

- 8 II. Hain in diesen Paradiesen 01:18

- 9 III. Als Neuling trat ich ein in dein Gehege 01:41

- 10 IV. Da meine Lippen reglos sind 01:28

- 11 V. Saget mir, auf welchem Pfade 01:12

- 12 VI. Jedem Werke bin ich fürder tot 00:59

- 13 VII. Angst und Hoffen wechselnd sich beklemmen 01:09

- 14 VIII. Wenn ich heut nicht deinen Leib berühre 00:57

- 15 IX. Streng ist uns das Glück und spröde 01:23

- 16 X. Das schöne Beet betracht ich mir im Harren 02:16

- 17 XI. Als wir hinter dem beblümten Tore 03:24

- 18 XII. Wenn sich bei heilger Ruh in tiefen Matten 01:59

- 19 XIII. Du lehnest wider eine Silberweide 01:33

- 20 XIV. Sprich nicht mehr von dem Laub 00:40

- 21 XV. Wir bevölkerten die abend-düstern Lauben 06:11

- Drei Klavierstücke, Op. 11

- 22 I. Mässig 04:11

- 23 II. Mässige 08:24

- 24 III. Bewegt 02:34

- Fünf Klavierstücke, Op. 23

- 25 I. Sehr langsam 02:38

- 26 II. Sehr rasch 02:00

- 27 III. Langsam 04:28

- 28 IV. Schwungvoll 02:48

- 29 V. Walzer 02:48

- Sechs kleine Klavierstücke, Op. 19

- 30 I. Leicht, zart 01:25

- 31 II. Langsam 01:02

- 32 III. Sehr langsam 00:50

- 33 IV. Rasch, aber leicht 00:21

- 34 V. Etwas rasch 00:29

- 35 VI. Sehr langsam 01:17

- Suite für Klavier, Op. 25

- 36 Präludium, Rasch 00:54

- 37 Gavotte - Musette 04:46

- 38 Intermezzo 05:32

- 39 Menuett 03:52

- 40 Gigue, Rasch 02:31

- Zwei Klavierstücke, Op. 33a & b

- 41 I. Mässig 02:43

- 42 II. Mässig, langsam 04:23

Info for The Music of Arnold Schönberg: Songs and Works for Piano Solo (Remastered)

Volume 1 of Schoenberg’s lieder, recorded between 11 June 1964 and 18 November 1965, marked a watershed in Gould’s career. Following Howard Scott, Joseph Scianni, Paul Myers, and finally Thomas Frost, the young Andrew Kazdin now shouldered the fascinating if awesome responsibility of producing Gould’s recordings—an alliance that was to last almost fifteen years.

„If the songs and piano pieces of Arnold Schoenberg were cool, calm, and completely objective, Glenn Gould's recordings of them would be ideal. In the songs -- the Zwei Gesänge, Op. 1; the Vier Lieder, Op. 2; and the 15 songs of Das Buch der Hängenden Gärten, Op. 15 -- Gould's detached touch, precise articulation, and very discrete use of the sustain pedal reveals every note of the accompaniment with astounding clarity. In the piano pieces -- the Drei Klavierstücke, Op. 11; the Sechs Kleine Klavierstücke, Op. 19; the Fünf Klavierstücke, Op. 23; the Suite for Klavier, Op. 25; and the Zwei Klavierstücke, Op. 33 A & B -- Gould's dry tone, restrained dynamics, and disinclination to apply the sustain pedal creates virtual x-rays of the score with astonishing lucidity. And for those who prize clarity and lucidity above all else in Schoenberg, Gould's performances will be perfect.

But for those who prize emotion and expression above all else in Schoenberg, Gould's performances will be acutely disappointing. To them, the brutal dissonances, harsh harmonies, jagged textures, abrupt transitions, and violent rhythms of Schoenberg's music demand anguish and expressivity from the performers, and this Gould resolutely refuses to provide. Some might argue that hearing all the notes is the paramount criteria for any performance, and that one can indubitably hear everything in Gould's performances. But others might reply that it's possible to have both lucidity and expressivity and point to Maurizio Pollini's recordings of Schoenberg's piano pieces as proof. And still others might point out that one can hear too much in Gould's performances, to wit, Gould's own moaning vocalizations behind and beneath the music he's playing. Though his fans have learned to tolerate this eccentricity, many others have not, and listeners fresh to Gould should be warned of it beforehand.

As for the singers, bass-baritone Donald Gramm's tired tone makes it hard to listen to the Zwei Gesänge, soprano Ellen Faull's wobbly intonation makes it difficult to listen to the Vier Lieder, and mezzo-soprano Helen Vanni's screechy attack makes it almost impossible to listen to Das Buch der Hängenden Gärten. Recorded between 1959 and 1965, Columbia's stereo sound here is as cool and objective as Gould's performances.“ (James Leonard, AMG)

Glenn Gould, piano

Digitally remastered

Glenn Gould

was born in Toronto in 1932, and enjoyed a privileged, sheltered upbringing in the quiet Beach neighborhood. His musical gifts became apparent in infancy, and though his parents never pushed him to become a star prodigy, he became a professional concert pianist at age fifteen, and soon gained a national reputation. By his early twenties, he was also earning recognition through radio and television broadcasts, recordings, writings, lectures and compositions.

Early on, Gould’s musical proclivities, piano style and independence of mind marked him as a maverick. Favoring structurally intricate music, he disdained the early-Romantic and impressionistic works at the core of the standard piano repertoire, preferring Elizabethan, Baroque, Classical, late-Romantic and early-twentieth-century music; Bach and Schoenberg were central to his aesthetic and repertoire. He was an intellectual performer, with a special gift for clarifying counterpoint and structure, but his playing was also deeply expressive and rhythmically dynamic. He had the technique and tonal palette of a virtuoso, though he upset many pianistic conventions – avoiding the sustaining pedal, using détaché articulation, for example. Believing that the performer’s role was properly creative, he offered original, deeply personal, sometimes shocking interpretations (extreme tempos, odd dynamics, finicky phrasing), particularly in canonical works by Mozart, Beethoven and Brahms.

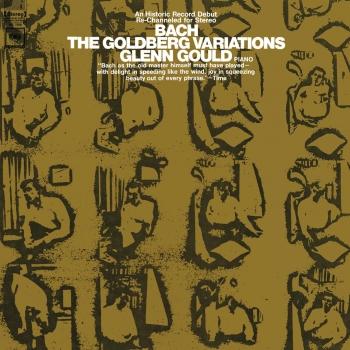

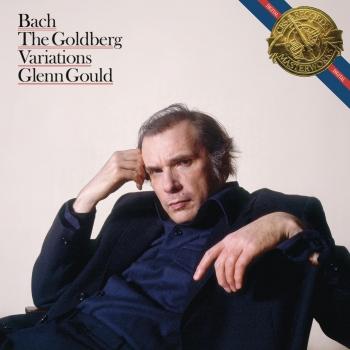

Gould’s American début, in 1955, and the release, a year later, of his first Columbia recording, of Bach’s Goldberg Variations, launched his international concert career. He earned widespread acclaim despite his musical idiosyncrasies, while his flamboyant stage mannerisms, as well as his hypochondria and other personal eccentricities, fuelled colorful publicity that heightened his celebrity. But he hated performing – ”At concerts I feel demeaned, like a vaudevillian” – and though in great demand, he rationed his appearances stingily (he gave fewer than forty concerts overseas). Finally, in 1964, he permanently retired from concert life.

Gould harbored musical, temperamental and moral objections to concerts, and aired them publicly: “The purpose of art,” he wrote, “is not the release of a momentary ejection of adrenalin but is, rather, the gradual, lifelong construction of a state of wonder and serenity.” Even before he retired, he was not satisfied with being a concert pianist; he made radio and television programs, published writings on many musical and non-musical topics, continued to compose. After 1964, this work away from the piano only intensified. He liked to call himself “a Canadian writer, composer, and broadcaster who happens to play the piano in his spare time.”

His retirement was also fuelled by his devotion to the electronic media. Gould was one of the first truly modern classical performers, for whom recording and broadcasting were not adjuncts to the concert hall but separate art forms that represented the future of music. He made scores of albums, steadily expanding his repertoire and developing a professional engineer’s command of recording techniques. He also wrote prolifically about recording and the mass media, his ideas often harmonizing with those of his friend Marshall McLuhan.

Though he never became the significant composer that he longed to be, Gould channeled his creativity into other media. In 1967, he created his first “contrapuntal radio documentary,” The Idea of North, an innovative tapestry of speaking voices, music and sound effects that drew on principles from documentary, drama, music and film. Over the next decade, he made six more such specimens of radio art, in addition to many other, more conventional, recitals and talk-and-play shows for radio and television. He also arranged music for two feature films.

Gould lived a quiet, solitary, spartan life, and guarded his privacy; his romantic relationships with women, for instance, were never made public. (“Isolation is the one sure way to human happiness.”) He maintained a modest apartment and a small studio, and left Toronto only when work demanded it, or for an occasional rural holiday. He recorded in New York until 1970, when he began to record primarily at Eaton Auditorium in Toronto.

In the summer of 1982, having largely exhausted the piano literature that interested him, he made his first recording as a conductor, and he had ambitious plans for several years’ worth of conducting projects; he planned then to give up performing, retire to the countryside, and devote himself to writing and composing. But shortly after his fiftieth birthday, Gould died suddenly of a stroke.

Since then, he has enjoyed a remarkable posthumous “life.” His multifarious work has been widely disseminated. He has been the subject of an enormous and diverse literature in many languages. And he has inspired conferences, exhibitions, festivals, societies, radio and television programs, novels, plays, musical compositions, poems, visual art and a feature film (Thirty-Two Short Films About Glenn Gould).

Moreover, his ideas – like McLuhan’s – still resonate strongly today in the world of digital technology, which was in its infancy when he died. His postmodernist advocacy of open borders between the roles of composer, performer and listener, for instance, anticipated digital technologies (like the Internet) that democratize and decentralize the institutions of culture. There is no question that Gould, more than any other classical musician, would have understood and admired digital technology – and would have had fun playing with it. (Kevin Bazzana)

Booklet for The Music of Arnold Schönberg: Songs and Works for Piano Solo (Remastered)