Friedrich Gulda, Wiener Philharmoniker & Claudio Abbado

Biography Friedrich Gulda, Wiener Philharmoniker & Claudio Abbado

Friedrich Gulda

Gulda’s first tuition was at the Grossman Conservatory where between the ages of eight and twelve his teacher was Felix Pazofsky. At twelve he entered the Vienna Academy of Music where he studied piano with Bruno Seidlhofer and theory with Joseph Marx. After making his debut at the age of fourteen, Gulda went on to win the Geneva Piano Competition in 1946, subsequently touring Switzerland, Italy, Hungary and Czechoslovakia. Gulda rapidly gained an international reputation and gave his Carnegie Hall debut in 1950. His repertoire at this time concentrated on Bach, Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert; he gave complete cycles of the Beethoven sonatas, and played chamber music. During the 1950s he made a series of recordings for Decca, but in 1962 his career took a very different turn.

Disillusioned with the life of a virtuoso, Gulda turned his attention to jazz. He had already appeared with the Austrian All Stars on radio in 1956, and in the same year at New York’s famous Birdland, as well as at the Newport Jazz Festival. However, by the early 1960s Gulda had formed a small jazz group and a big band called the Eurojazz Orchestra. He played the wooden flute and baritone saxophone and composed his own works for jazz combinations. Gulda gave up the leadership of the Eurojazz Orchestra in 1966, founding a jazz competition in Vienna and opening a school of improvisation in Ossiach.

During the next three decades Gulda performed jazz and classical music, often together, juxtaposing both forms to stimulate his audiences. In 1990 he formed his Paradise Band with whom he gave performances combining Mozart, jazz improvisation and nightclub dance acts. Gulda worked with pianist Chick Corea, and, in the 1980s, with soprano Jessye Norman.

In the recording of Debussy’s préludes for Decca made in 1955 Gulda’s improvisatory qualities can be heard in Feuilles mortes, where his placing of chords is somewhat reminiscent of jazz pianist Bill Evans, and the whole piece has an air of being created on the spot (although perhaps without knowing of Gulda’s jazz career one would not think this). Of his Decca LP of the Chopin ballades, The Gramophone magazine stated, ‘…one will listen in vain for many traces of poetry or understanding. Gulda seems, at the start of each Ballade, to be waiting impatiently for the moment when he can bang off into specious virtuosity.’

In the late 1960s and early 1970s Gulda recorded Bach’s Das wohltemperierte Klavier complete and all of Beethoven’s piano sonatas. The sonatas, all of which he had previously recorded for Decca between 1950 and 1958, were recorded again for Amadeo in 1967 and were described in 1970 as playing that is ‘…architecturally clear, rather objective, and often quite astonishing in its uncomplicated directness. Those who favour tremendous colouristic variety and metaphysical philosophising had better look elsewhere…’ The reviewer goes on to describe the playing as being at times ‘downright brutal and aggressive’. Some of the Amadeo sonata recordings were issued on compact disc by Philips, and in 2005 Decca issued the earlier sonata cycle on eleven compact discs in their Original Masters Series. Gulda’s 1968 recording of Beethoven’s ‘Diabelli’ Variations Op. 120 has been described as ‘modernist’ and he plays with no repeats. Chamber music includes Beethoven cello sonatas with Pierre Fournier recorded in 1959, and Strauss lieder with Hilde Gueden.

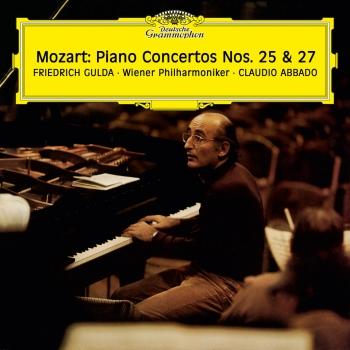

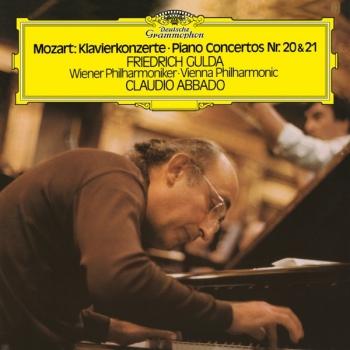

In the mid 1970s Gulda recorded some Mozart piano concertos for Deutsche Grammophon with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra and Claudio Abbado. These are fine performances with the added interest in K. 467 and K. 503 of cadenzas by Gulda himself. In an interesting disc from the mid-1980s of the Concerto for Two Pianos K. 365, Gulda is partnered by jazz pianist Chick Corea. Also on the disc are Corea’s Fantasy for Two Pianos and Gulda’s jazz-inspired Ping Pong for two pianos.

Gulda was obviously a man who did not like any form of restriction. After his series of Decca recordings in the 1950s, he changed label and producer many times. His unorthodox attitudes led him to want to shock his audiences for classical music, and give performances that were both challenging and uncompromising.