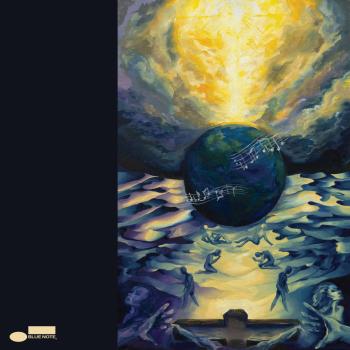

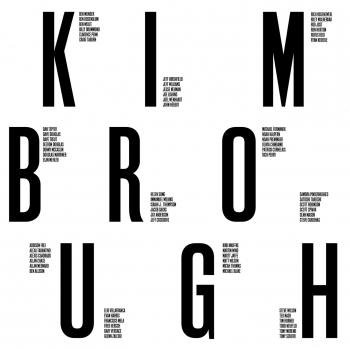

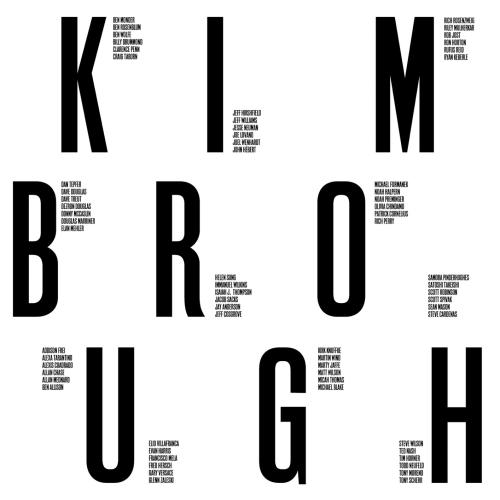

Kimbrough Various Artists - Kimbrough

Album Info

Album Veröffentlichung:

2021

HRA-Veröffentlichung:

16.07.2021

Das Album enthält Albumcover Booklet (PDF)

- 1 The Call 07:34

- 2 C Minor Waltz 04:58

- 3 Kudzu 07:24

- 4 Elegy for P.M. 04:35

- 5 Falling Waltz 05:13

- 6 Forsythia 06:49

- 7 Quickening 04:04

- 8 Whirl 03:32

- 9 Wings 04:15

- 10 Hope 06:41

- 11 Clara's Room 05:34

- 12 For Duke 04:15

- 13 Lullabluebye 07:26

- 14 For Jimmy G. 05:54

- 15 November 06:49

- 16 Adrian's Way 05:42

- 17 Sadness 05:13

- 18 Helix 05:59

- 19 The Breaks 05:06

- 20 20 Bars 07:30

- 21 Ancestors 06:12

- 22 Kids Stuff 04:57

- 23 Meantime 05:37

- 24 Capricorn Lady 05:37

- 25 Waltz for Lee 04:43

- 26 727 04:52

- 27 Beginning 04:47

- 28 Southern Lights 04:56

- 29 Regeneration 07:08

- 30 A & J 05:48

- 31 Eventualities 06:15

- 32 Moonflower 02:24

- 33 Just Suppose 05:01

- 34 Reluctance 06:55

- 35 Areas 03:36

- 36 The Spins 05:31

- 37 Sanibel Island 05:04

- 38 Fubu 06:55

- 39 Cascade Rising 05:14

- 40 Over 03:57

- 41 Blue Smoke 03:47

- 42 Air 04:22

- 43 Affirmation 04:17

- 44 Quiet as It's Kept 06:09

- 45 TMI 07:57

- 46 Time Will Tell 06:42

- 47 Areas (Version 2) 04:41

- 48 Noumena 05:15

- 49 Sloppy Seconds 05:20

- 50 Reluctance (Solo Piano) 04:11

- 51 Grass Valley 06:20

- 52 Questions the Answer 05:28

- 53 Lucent 06:06

- 54 No Radio 04:26

- 55 For Carla 03:24

- 56 Ode 03:40

- 57 St. Mark's Place 05:24

- 58 Ca'lina 05:56

- 59 Hymn 04:05

- 60 Svengali 11:05

- 61 For Duke (Vocals) 04:56

Info zu Kimbrough

This is our tribute to the legendary artist and educator Frank Kimbrough. A collection of 61 original compositions by Frank, featuring 67 of his former bandmates, students, and friends across multiple generations.

The album was recorded over three and a half days in New York as the musical world began reawakening in May 2021. All proceeds from this definitive collection of Frank’s music, available on high-quality digital download on Bandcamp, will benefit the Frank Kimbrough Jazz Scholarship at The Juilliard School.

Liner Notes: I like to imagine Frank sitting on a bench in the little park by his apartment in Queens, or perhaps strolling through Central Park. Maybe it’s 1996 and he’s got that ponytail, or maybe it’s 2016 and he’s got his Juilliard-professor-look going. Either way, it’s about 11:00 PM, he’s got that half smile on his face that he was a little infamous for, one arm draped over the back rest, or slightly swinging at his sides and he’s catching a melody.

There’s something insubstantial about a jazz composition. Often just one page long, single notated lines over chord symbols — little translucent scraps of melody and harmony, a lens to see the world through — an opening. I struggle sometimes with the juxtaposition of process and import. Supposedly, Duke Ellington wrote “Solitude” in 20 minutes because his band needed one more tune for a record date. Wayne Shorter is one of the most remarkable musicians of the 20th century, but you wouldn’t necessarily be wrong in saying his greatest achievement was the morning he spent writing the 16 measures of “Nefertiti.” What a thought!

Frank didn’t so much compose songs as discover them. He wrote almost all of them while wandering through the city. I want to call him a nocturnal lepidopterist, out with his butterfly net in the odd corners of the city but that’s not really it. He wasn’t precious about it, he didn’t catalog his tunes, and he wasn’t thirsting for any kind of rare discovery. Frank wrote music the same way he improvised, less the Nabokovian madman with the net and more like that lady in Washington Square Park who feeds all the squirrels. The music came to him.

As a student of Frank’s I used to marvel at his ability to hear music away from the piano. He had perfect pitch and a preternatural ability to hear polyphony in his head. He could hear these huge nine-note chords spelled out, not unheard of amongst professional musicians, but Frank brought a certain effortlessness to it. It felt superhuman to me, like he had some kind of supercomputer in his brain doing double-time computations. But Frank was also the man famous for the “hang.” He was the guy you had three hour dinners with, or went on five hour walks with. Frank’s approach wasn’t about feats of uncanny ear training. He didn’t practice music away from the piano just because he could, he did it because that’s where the music was. The music is not in the practice room, and it’s not on the cell phone (which Frank never owned, a remarkable achievement for a freelancing musician reliant on getting called for gigs). You have to go out in the world and be present for it. The music is the city, the parks, and the quiet of a nighttime stroll, but mostly, the music is other people. It’s the connections you build that make you the musician that you are. I never realized this until after Frank died, but for me he came closest to marrying the spirit of musical improvisation to the way he lived. Frank’s genius was profoundly human.

You only have to listen to a couple of these songs to hear how much Frank was loved in this community. During the session, there was a lot of awkward elbow/fist-bump-Covid handshakes and a general feeling of surreality just to be sharing space with other humans. But then the music would start and it was absolutely thrilling, as if all of this kinetic energy had been stored up over the past 14 months just looking for an outlet. There are 67 musicians on this record and we recorded 61 tracks in three and half days. I felt like I was floating in air through most of it. It was a very ambitious project that somehow ran ahead of schedule. We even captured 7 extra songs that we didn’t plan on as people flipped through Frank’s tunes asking, “Hey, can the four of us try this one?” Most of the ensembles had at least two people that had never played together. Some musicians were reuniting to play together for the first time in decades. There are at least four generations of musicians represented on this record, students, colleagues, friends and bandmates of Frank, all wanting to pay tribute. And of course, maybe the biggest tribute was to have Frank pull us all together, for one big hang, after this god-awful year.

But I keep coming back to these tunes. When I envisioned this project, I had about 15 charts of Frank’s and I figured I could rustle up a couple more. When I got in touch with Ron Horton, he offered to scan and send over what he had from Frank’s files and his own archives. He sent me 90 tunes. I’ve spent the last couple of months playing these tunes, both at the piano and as I wander my own environment. Some I knew, many I never heard, many have never been recorded. I was struck by their integrity and consistency. Frank knew exactly what he was about even back in 1979. He never wrote something just to try out a new style or a concept. They are strikingly specific in their shape, as far as I can tell he had to essentially create his own harmonic vocabulary just to capture what he was hearing, and yet they are wide open in the particulars. That reminds me of Monk and Wayne Shorter. Duke too. Frank would argue strenuously to the contrary, but I’m comfortable putting Frank in the conversation with any of the great jazz composers. There’s so much life in this music and it makes me miss Frank too god-damned much.

I get great comfort from hearing a miniature reflection of Frank’s life in this record. All those relationships that Frank fostered bouncing off each other – an afterglow of all the love Frank put out in the world. Our legacies live, not in the monuments we leave behind, but in the way things spin forward from us. So, despite the inspiration I feel in holding Frank’s book of music in my hands, I know that these musical haikus don’t encapsulate a life. But when I flip through these songs, and hear clumsily in my head what Frank heard in brilliant color, what comes to mind is a roadmap for how one man can sit on a park bench in Queens and change the world. By Elan Mehler

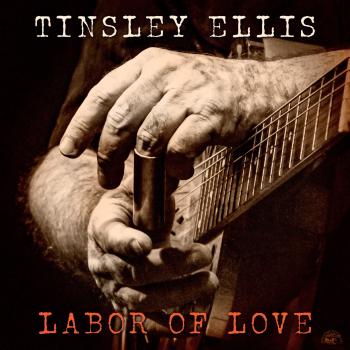

David ‘Junior’ Kimbrough

David 'Junior' Kimbrough wurde am 28. Juli 1930 in Hudsonville, Mississippi, nahe der Grenze zu Tennessee geboren. Während die Familie auf dem Feld schuftete, schnappte sich der kleine Junior heimlich die Gitarre seines Vaters. Bei diesen ersten Versuchen brachte er sich selbst genug bei, um dem zukünftigen Rockabilly-Sänger Charlie Feathers ein paar Gitarrenstunden zu geben, als beide noch kleine Jungs waren (Feathers war von Kimbroughs Blues so begeistert, dass er ihn "den Anfang und das Ende aller Musik" nannte). In den 50ern wurde sein Sound härter, aber Kimbrough tat sich weiterhin schwer, auf sich aufmerksam zu machen.

Erst 1966 absolvierte er seine ersten Aufnahmen, doch der Produzent Quinton Claunch aus Memphis brachte nichts davon auf den Markt. Das winzige Philwood-Label gab Junior ein Jahr später eine Chance und veröffentlichte seine Debütsingle unter dem Namen Junior Kimbell. Man hörte Kimbrough auch danach fast nur in lokalen Juke-Joints, bis er 1992 dank der Aktivitäten des Autors Robert Palmer, der Juniors einmaligen Sound in seinem gewohnten Umfeld einfing, einen kleineren Durchbruch schaffte. Sein erstes Album für das neue Label Fat Possum, 'All Night Long', wurde live mit seiner Rhythmusgruppe eingespielt: Bassist Garry Burnside (der Sohn seines Lokalrivalen R.L. Burnside) und Juniors eigener Sohn, Kenny Malone, am Schlagzeug. Klar strukturierte Akkordwechsel waren kein Thema; Kimbroughs modaler Ansatz, seine schneidende E-Gitarre und ein Gesangsstil, der nicht weit vom archaischen Field Holler entfernt ist, waren Elemente früherer Traditionen, doch brachte er das Ganze in zeitgemäßer Weise rüber.

Durch 'All Night Long' und seinen sehr stimmungsvollen Auftritt in Robert Mugges 1992er-Dokumentarfilm über den Mississippi-Blues, 'Deep Blues' (geschrieben und präsentiert von Palmer), erfuhr Kimbrough endlich eine gewisse nationale Anerkennung. Er nahm weitere CDs für Fat Possum auf, doch er konnte wegen gesundheitlicher Probleme kaum auf Tour gehen. Als Kimbrough am 17. Januar 1998 in Holly Springs, Miss., verstarb, war er in Blueskreisen dennoch weit über seine ländliche Heimat in Mississippi hinaus bekannt.

Booklet für Kimbrough