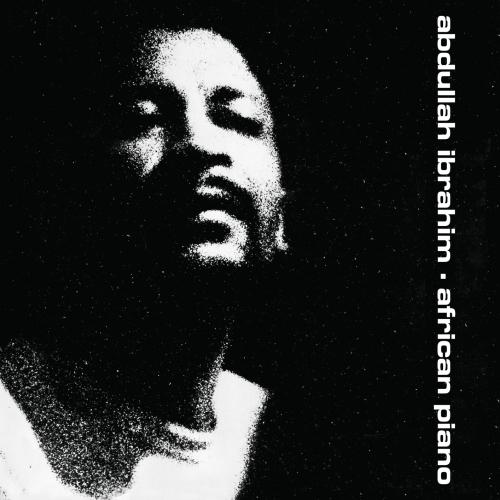

African Piano Abdullah Ibrahim (Dollar Brand)

Album Info

Album Veröffentlichung:

2014

HRA-Veröffentlichung:

21.01.2014

Das Album enthält Albumcover Booklet (PDF)

Entschuldigen Sie bitte!

Sehr geehrter HIGHRESAUDIO Besucher,

leider kann das Album zurzeit aufgrund von Länder- und Lizenzbeschränkungen nicht gekauft werden oder uns liegt der offizielle Veröffentlichungstermin für Ihr Land noch nicht vor. Wir aktualisieren unsere Veröffentlichungstermine ein- bis zweimal die Woche. Bitte schauen Sie ab und zu mal wieder rein.

Wir empfehlen Ihnen das Album auf Ihre Merkliste zu setzen.

Wir bedanken uns für Ihr Verständnis und Ihre Geduld.

Ihr, HIGHRESAUDIO

- 1 Bra Joe from Kilimanjaro 11:11

- 2 Selby That the Eternal Spirit Is the Only Reality 02:23

- 3 The Moon 08:08

- 4 Xaba 00:41

- 5 Sunset in Blue 04:25

- 6 Kippy 05:05

- 7 Jabulani - Easter Joy 02:07

- 8 Tintiyana 04:45

Info zu African Piano

African Piano was a highly influential album, and it has lost none of its power – as can be heard on this HighResAudio reissue. Released for the first time under the name Abdullah Ibrahim instead of the pianist’s original „Dollar Brand“ sobriquet.

Sometimes a musical message is so urgent that questions of recording quality are almost beside the point. Informally recorded in 1969 in a noisy club – Copenhagen’s famous Jazzhus Montmartre – the flavour of this album is ‘documentary’ rather than luxuriantly hi-fidelity, yet the essence of Abdullah Ibrahim’s communication comes through loud and clear. The listener is drawn into the robust rhythms of his solo piano style, as he re-examines the history of jazz from a South African perspective, with echoes of songs of the townships, and vamps that hint of Monk and Duke and much more. African Piano was a highly influential album, and it has lost none of its power.

South African pianist-composer Abdullah Ibrahim, still performing at the time of this 1969 live album under the pseudonym Dollar Brand, unleashed a mastery so enticing on African Piano, it’s a wonder that any of the folks at the club where it was recorded had the resolve to treat it as background to their dining. By the same token, reinforcement of that fact by constant ambient noises renders Ibrahim’s performance all the more sacred by contrast.

Amid a sea of chatter, cleared throats, and sudden intakes of breath, he breaks the surf with the gentle yet hip ostinato of “Bra Joe From Kilimanjaro,” working meditative tendrils into the bar light. Over this his right hand brings about an explosive sort of thinking that spins webs in a flash and connects them to larger others. With clarion fortitude, he drops bluesy accents along the way: a trail of crumbs leading to “Selby That The Eternal Spirit Is The Only Reality.” Ironically (or not), this is the most solemn blip on the album’s radar and blends into the ivory tickling of “The Moon.” Here Ibrahim’s heartfelt, dedicatory spirit comes to the fore, proving that, while technically proficient, he possesses a descriptive virtuosity that indeed evokes a pockmarked surface lit in various phases, harnessing sunlight as if it were skin in dense, vibrating harvest. The kinesis of this tune is diffused in the tailwind of “Xaba,” which then flows into “Sunset In Blue,” in which Ibrahim’s ancestral awareness is clearest. The level of respect evoked here for both the dead and the living lends a ritualistic quality by virtue of its tight structuring, which despite hooks at the margins flies freely in its magic circle. “Kippy” is a smoother reverie with flickers of flame. A beautiful amalgam of measures and means, it slips an opiate of reflection into its own drink. After this, the intense two minutes of gospel and downward spirals that is “Jabulani—Easter Joy” takes us into “Tintinyana,” thereby crystallizing the album’s flowing energies. Tracks bleed into one another: they runneth from the same cup, their spiritual resonance deep and true.

African Piano is a gorgeous, thickly settled album, but one that is always transparent when it comes to origins. Such is the tenderness of Ibrahim’s craft, which speaks with a respect that transcends the sinews, muscles, and eardrums required to bring it to life. It finds joy in history, connecting to it like an Avatar’s tail to steed.

„Pianist Abdullah Ibrahim was still known as 'Dollar Brand' when he recorded this solo piano set for ECM; it has been reissued on CD under his original name. The continuous live performance (which is under 39 minutes) explores eight of Ibrahim's originals...Ibrahim was still in the process of finding his own sound at the time, although his improvisations (which use repetition and vamps effectively) have their interesting moments. Still, Ibrahim's later work is more significant.“ (Scott Yanow)

Abdullah Ibrahim, piano

Recorded live on October 22, 1969 at Jazzhus Montmartre, Copenhagen

Digitally remastered by ECM.

Abdullah Ibrahim (Dollar Brand)

South Africa’s most distinguished pianist and a world-respected master musician, was born in 1934 in Cape Town and baptized Adolph Johannes Brand. His early musical memories were of traditional African Khoi-san songs and the Christian hymns, gospel tunes and spirituals that he heard from his grandmother, who was pianist for the local African Methodist Episcopalian church, and his mother, who led the choir. The Cape Town of his childhood was a melting-pot of cultural influences, and the young Dollar Brand, as he became known, was exposed to American jazz, township jive, CapeMalay music, as well as to classical music. Out of this blend of the secular and the religious, the traditional and the modern, developed the distinctive style, harmonies and musical vocabulary that are inimitably his own.

He began piano lessons at the age of seven and made his professional debut at fifteen, playing and later recording with such local groups as the Tuxedo Slickers. He was in the forefront of playing bebop with a Cape Town flavour and 1958 saw the formation of the Dollar Brand Trio. His groundbreaking septet the Jazz Epistles, formed in 1959 (with saxophonist Kippie Moeketsi, trumpeter Hugh Masekela, trombonist Jonas Gwanga, bassist Johnny Gertze and drummer Makaya Ntshoko), recorded the first jazz album by South African musicians. That same year, he met and first performed with vocalist Sathima Bea Benjamin; they were to marry six years later.

After the notorious Sharpeville massacre of 1960, mixed-race bands and audiences were defying the increasingly strict apartheid laws, and jazz symbolized resistance, so the government closed a number of clubs and harassed the musicians. Some members of the Jazz Epistles went to England with the musical King Kong and stayed in exile. These were difficult times in which to sustain musical development in South Africa. In 1962, with Nelson Mandela imprisoned and the ANC banned, Dollar Brand and Sathima Bea Benjamin left the country, joined later by the other trio members Gertze and Ntshoko, and took up a three-year contract at the Club Africana in Zürich. There, in 1963, Sathima persuaded Duke Ellington to listen to them play, which led to a recording session in Paris – Duke Ellington presents the Dollar Brand Trio – and invitations to perform at key European festivals, and on television and radio during the next two years.

In 1965, the now married couple moved to New York. After appearing that year at the Newport Jazz Festival and Carnegie Hall, Dollar Brand was called upon in 1966 to substitute as leader of the Ellington Orchestra in five concerts. Then followed a six-month tour with the Elvin Jones Quartet. In 1967 he received a Rockefeller Foundation grant to attend the Juilliard School of Music. Being in the USA also afforded him the opportunity to interact with many progressive musicians, including Don Cherry, Ornette Coleman, John Coltrane, Pharaoh Sanders, Cecil Taylor and Archie Shepp.

The year 1968 was a turning point. Searching for spiritual harmony in an increasingly fractured life, Dollar Brand went back to Cape Town, where he converted to Islam, taking the name Abdullah Ibrahim, and in 1970 he made a pilgrimage to Mecca. Music and martial arts further reinforced the spiritual discipline he found. After a couple of years based in Swaziland, where he founded a music school, Abdullah and his young family returned in 1973 to Cape Town, though he still toured internationally with his own large and small groups. In 1974 he recorded “Mannenberg – ‘Is where it’s happening’”, which soon became an unofficial national anthem for black South Africans. After the Soweto student uprising, in 1976, he organized an illegal ANC benefit concert; before long, he and his family left for America, to settle once again in New York.

Determined to manage his own affairs in America, he founded with Sathima, the record company Ekapa in 1981. The 1980s saw him involved with a range of artistic projects that depended on his music: Garth Fagan’s ballet Prelude (first performed 1981), the Kalahari Liberation Opera (Vienna, 1982), and in 1983 a musical, Cape Town, South Africa, featuring the septet he formed that year, Ekaya. In 1987, he played a memorial concert for Marcus Garvey in London’s Westminster Cathedral, and the following year he played at the concert in Central Park, New York, commemorating the seventieth birthday of Nelson Mandela.

In 1990 Mandela, freed from prison, invited him to come home to South Africa. The fraught emotions of reacclimatizing there are reflected in Mantra Modes (1991), the first recording with South African musicians since 1976, and in Knysna Blue (1993). He memorably performed at Mandela’s inauguration in 1994.

Abdullah Ibrahim has been the subject of several documentaries: for instance, Chris Austin’s 1986 BBC film A Brother with Perfect Timing, and A Struggle for Love, by Ciro Cappellari (2004). He has also composed scores for film, including the award-winning soundtrack for Claire Denis’s Chocolat (1988), as well as for No Fear, No Die (1990) and Idrissa Ouedraogo’s Tilai (1990), and he was featured in the 2002 production Amandla: A Revolution in Four-Part Harmony.

For more than a quarter-century he has toured the world extensively, appearing at major concert halls, clubs and festivals, giving sell-out performances, as solo artist or with other renowned artists (notably, Max Roach, Carlos Ward and Randy Weston). His collaborations with classical orchestras have resulted in acclaimed recordings, such as African Suite (1999, with members of the European Union Youth Orchestra) and the Munich Radio Philharmonic orchestra symphonic version, “African Symphony” (2001), which also featured the trio and the NDR Jazz Big Band..

Abdullah Ibrahim celebrated his seventieth birthday in October 2004, which occasion was marked by the release of two CDs by Enja Records (the Munich-based label with whom he has recorded for three decades): the compilation A Celebration, and Re:Brahim, his music remixed. His discography runs to well over a hundred album credits

When not touring, he now divides his time between Cape Town and New York. In addition to composing and performing, he has started a South African production company, Masingita (Miracle), and established a music academy, M7, offering courses in seven disciplines to educate young minds and bodies. Most recently, in 2006, he spearheaded the historic creation (backed by the South African Ministry of Arts and Culture) of the Cape Town Jazz Orchestra, an eighteen-piece big band, which is set to further strengthen the standing of South African music on the global stage.

A martial arts Black Belt with a lifelong interest in zen philosophy, he takes every opportunity to visit his master in private trips to Japan. In 2003 he performed charity concerts at temples in Kyoto and Shizuoka, the proceeds going to the M7 academy.

Booklet für African Piano