Lucky Thompson

Biographie Lucky Thompson

Lucky Thompson

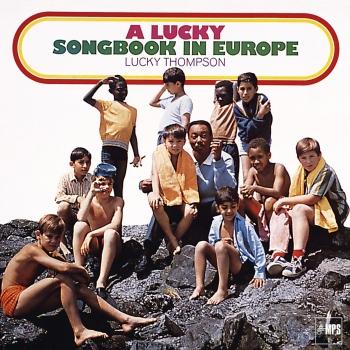

In 1968, saxophonist Lucky Thompson moved back to Europe with his family after a five-year stay in the States. He settled in Lausanne, Switzerland, which allowed him to tour in European cities where he found the most work. A year later, in March 1969, he recorded A Lucky Songbook in Europe for MPS, one of the Continent's great labels. The album would become one of Thompson's finest works.

Lucky Thompson's first trip to Europe came in 1956, when he relocated to Paris. While he was there, he joined the reed section of Stan Kenton's orchestra when Kenton was short a baritone saxophonist after Jack Nimitz failed to make the trans-Atlantic tour. When the Kenton orchestra returned to the States, Thompson recorded with the band on Cuban Fire starting in May. Overall, the tour was a rather awkward fit for Thompson, since by the 1950s, his instrumental poetry was better suited to smaller ensembles. The blessing for Thompson is that he fell hard for European life. He returned to Paris for an extended stay in '57, which enabled him to play the city's many clubs and tour regionally. He remained in Paris until late 1962, when he moved back to the States before his move to Switzerland in '68.

If you look at Thompson's years of migration, he couldn't have picked worse times to relocate. He left the States in '57 just as jazz recording was picking up following the release of the 12-inch LP in 1956 and launch of stereo in 1958. Then he returned to the States at the dawn of the pop-rock era, when recording work and gigs were drying up for jazz artists who weren't household names or studio musicians. On the other hand, Thompson seemed to suffer from mental illness and depression, so a more tranquil, integrated environment with access to healthcare surely meant more than hustling for scraps of opportunity.

The good news for Lucky is that Europe was his oyster and he was highly appreciated there, which kept him busy. He also was more comfortable in Europe as a creative artist. But as a result of his detachment from the U.S. jazz scene, Thompson was one of only a few jazz giants who really can't be classified as a member of one jazz school or another. In essence, if you combine the toughness of Coleman Hawkins and relaxed tones and agility of Lester Young, you'd probably come close to Thompson's sound. [Photo above of Lucky Thompson and British pianist Stan Tracey]

Thompson also was magnificently inventive as a composer and particularly graceful and slippery on song introductions and improvisational passages. He had great training. Thompson had worked with Count Basie in 1944 and '45 and then Boyd Raeburn in '45, two challenging bands. He also worked and recorded with plenty of small groups, including dates with Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie.

On March 13, 1969, after a flurry of written pleas by the team at MPS in Germany, Thompson finally agreed to record an album for the label at its studios in Villingen, in the Black Forest. Thompson, it turns out, was a perfectionist and something of a gentle control freak. According to the original liner notes for A Lucky Songbook in Europe by album producer Joachim Berendt (above), Thompson hand-picked each musician and insisted they be on the date.

Lucky Thompson was the bridge between swing and bebop. Lucky, Dexter Gordon and Don Byas were among the ones who showed up in New York at the time when the transition had to be made. Lucky had the brains, which was why Bird and others included him on their sessions. He wasn't the most technically proficient guy, on the level of a Bird or a Sonny Rollins, but he had the brains to overcome his technical limitations. And, like all of the musicians who decide to put in the work of a craftsman and learn the music from the ground up, he had his own sound. You don't have to look at any one aspect of his playing; Lucky was just his own person.

I was fortunate enough to meet Lucky in 2002. A guy named Philip Cody and his wife, Evie, had gotten to know Lucky and were going to visit him in the nursing home where he lived in Seattle. Phil emailed me and asked if I wanted to meet Lucky Thompson, so I just picked myself up and went along with my dad, who was also with me on the West Coast. I had heard that Lucky didn't talk, but he talked to us. I think music meant more to him than he let on, but it had disappointed him so much. He had that distant look on his face, but he asked me my name, and we talked--about music, not about him. He picked up my tenor and just popped the keys and said, "This horn has a sound," just popping the keys and looking at me. Then he asked me to play tunes, a lot of which were things from the '30s that I didn't know. I wish I had written them down and learned them. Then he asked me to play like Charlie Parker and like Sonny, and he liked that. He claimed that he didn't remember any of his music, but I had brought some of his records with me, and when I played Lucky Strikes he froze. Then he started telling stories about the musicians on the date.