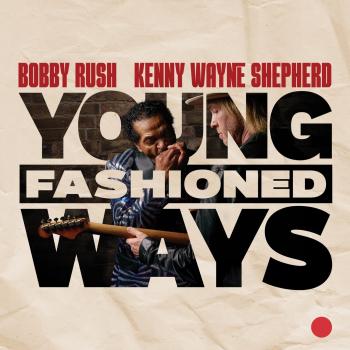

Bobby Rush & Kenny Wayne Shepherd

Biographie Bobby Rush & Kenny Wayne Shepherd

Bobby Rush

3x GRAMMY winning legend, Blues Hall of Famer, six-time Grammy nominee, and 18-time Blues Music Award winner, with cameo in the Netflix original Dolemite Is My Name starring Eddie Murphy, and a recent Autobiography

During his renowned stage show Bobby Rush frequently jumps high into the air, arms spread and legs tucked, only to land gracefully and return without a hitch to his dazzling routine. It’s a move you might expect at a contemporary R&B show, but it’s downright shocking when you realize that Rush is in his late 80s.

“I never thought I would be here this long,” says Rush. “I was 83 years old before I won a Grammy, but it’s better late than never. I laugh about it, but I’m so blessed and I surely never thought I’d be making a living doing what I’m doing. I’m not just an old guy on my way out.”

Hardly. Rush’s busy schedule includes headlining European festivals with his band and solo programs at venues including Jazz at Lincoln Center, and he just recorded an album of brand new material, All My Love For You, coming out via his own label Deep Rush Records in collaboration with Nashville-based Thirty Tigers. Over the last several years he’s won a second Grammy, re-recorded his 1971 hit Chicken Heads together with his old friend Buddy Guy and young blues star Christone “Kingfish” Ingram, and written a critically acclaimed autobiography, I Ain’t Studdin’ You: My American Blues Story.

That story began in rural Homer/Haynesville, Louisiana, where Rush—born Emmett Ellis, Jr.—grew up on his family’s farm picking cotton, tending to mules and chickens, and living in a home without electricity nor indoor plumbing. He built his first guitar on the side of the family’s house out of broom wire, nails, bottles and bricks.

The blues, Rush recalls, provided “an escape from the cotton fields. You’d go out on Saturday night to the juke joints, but then on Monday morning you’d go back into the cotton fields to work for your bossman.”

He left behind farm work to perform on the road with the Rabbit Foot Minstrels, and as “Bobby Rush”—a name he took on out of respect to his father, a minister—he toured the jukes and clubs of Louisiana, Arkansas and Mississippi before settling in Chicago in the 1950s. Through singles on labels including Chess, ABC and Philadelphia International and relentless touring Rush established an unparalleled reputation as an entertainer, which later led to him being crowned by Rolling Stone magazine as King of the Chitlin’ Circuit, the network of African American clubs that arose during the segregation era.

Based in Jackson, Mississippi since the early ‘80s, Rush began “crossing over” to new audiences several decades ago, featured in the Martin Scorsese-produced documentary The Road to Memphis, appearing alongside Terrence Howard, Snoop Dogg and Mavis Staples in the documentary Take Me to the River, and performing on the Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon along with Dan Aykroyd. And the eternally youthful Rush was even able to play himself in the 1970s in Netflix's 2019 hit biopic Dolemite is My Name in a scene with Eddie Murphy. And the recognition keeps coming. In addition to his two Grammy wins (and six nominations), he’s in the Blues Hall of Fame, has won 16 Blues Music Awards (among 56 nominations), and there’s currently a musical in development called Slippin’ Through The Cracks with sights on Broadway, recently co-written by Rush and playwright Stephen Lloyd Helper, who co-wrote the 7x Tony-nominated musical Smokey Joe’s Café celebrating the songs of Lieber and Stoller.

Rush, meanwhile, still remains steadfastly committed to the African American audiences who sustained him for decades, and on his new album he looks back from his current vantage point as a seasoned artist celebrated by an ever-growing fan base.

“I put together all these songs when I was down with the COVID, thinking about where I was going to go from here. You’ll find everything about me inside these songs—folk funk, traditional blues, ballads, love, a comedy and a shit-talking. I don’t know if it hurts me, but my head just won’t let me be still.”

“The first song is, ‘I’m free, look at me. I’ve got the shackles off my feet and the chains off my mind.’ As a blues singer, as a Black man, there were a lot of places I could not go, a lot of things I could not do. But now I’m a free man, I can do some things I never did before and talk about some things I couldn’t talk about.”

In the romping autobiographical ‘I’m the One’ Rush celebrates his long history, including learned from B.B. King and Muddy Waters after arriving in Chicago in 1952. But he was always one to carve is own path, and relays here the challenges in his ultimately successful efforts to “bring the funk into the blues.”

“Back in the day it was hard for me to convince people about recording ‘Chicken Heads’ with that kind of beat—there was none of my peers cutting that kind of record. It was too funky.”

Most of the album finds Rush with new takes on the foibles of romance, addressing the sort of morality tales that he often acts out on stage with the help of his voluptuous dancers. Many of his songs over the years, such as “What’s Good For the Goose (Is Good For the Gander Too),” have drawn from the well of African American folklore, as does the first single off his new album, which revisits a classic that was recently covered by a young star of Southern Soul.

“King George had a record out called “Keep On Rollin,” and that really comes from a record I did 28 years ago called “One Monkey Don’t Stop No Show,” which was about woman who said she was going to leave me. So I now have a single, “One Monkey Can Stop a Show”—I’m going to treat her better so she sticks around.”

Rush advocates body positivity in celebrating his “TV Mama” ‘with the big wide screen,’ and in “I’ll Do Anything For You” proclaims that he’ll serve as his lover’s chauffer and masseuse, sleep out in the rain, and even rescue her from the jungle.

“I joke and talk about sex in a way that people can understand. I’m all for lifting it up, because if it wasn’t for sex, none of us would be here. That’s what the world is built around, making love and making money. I’m in the position now that I can tell the story better than most people, and plus I’ve got nothing to lose now.”

Rush has become one of the most prominent advocates for the blues tradition, and says “it’s the root of all music, it’s the mother of all music. If you don’t like the blues, you probably don’t like your mama.”

And he has no plans to slow down.

“I’m still in decent health and my mind is pretty keen, and the most blessed thing is that I still have people around me who love what I do. And even if you don’t like me, you’re still going to say, “I don’t like Bobby Rush, but, damn, he’s good.’

Kenny Wayne Shepherd

Put an ear to the door of FAME Studios in Muscle Shoals, Alabama, back in late 2019 and you’d have heard it. The first stirrings of a new studio album from the man who pulled American roots into the 21st century. Melodies forming, riffs taking shape, grooves building, stories of loss and redemption spun by a crack team of sympatico songwriters. The road from that first writing session to the finished copy of Dirt On My Diamonds you hold in your hands, smiles Kenny Wayne Shepherd, has been quite a ride. “Every record I make is a moment in time. And this is a really special moment.”

Since the release of his debut album, 1995’s Ledbetter Heights, this Grammy-nominated, multi-platinum bandleader still sounds like the future of the blues. Approach Dirt On My Diamonds expecting autopilot twelve-bars and you’ll instead be thrown a volley of curveballs, from the modern urban edge of Sweet & Low and Best Of Times’ socio-political observations to the speaker-tearing production from Shepherd and his partner-in-sound of recent years, Marshall Altman. “Working with Marshall, it’s like any productive relationship,” considers the guitarist. “We put our strengths together and push each other.”

Throughout, as the album title suggests, the grit and emotional honesty of these new songs is prized above guitar pyrotechnics (even for one of the modern scene’s most valuable players). Of the Dirt On My Diamonds’ guiding philosophy, “Life has imperfections, and I actually prefer it that way. The imperfections are what make it interesting.”

Since his birth in North Louisiana, in 1977, Shepherd’s own life has never followed the script. Steeped in classic blues and rock ‘n’ roll from an early age by his dad – a respected Louisiana radio personality and promoter – the kid soon reached for his first Fender Stratocaster and found he didn’t require lessons to make it cry and wail. Long before Warner Brothers subsidiary Giant Records offered a deal, Shepherd had clocked up countless miles on a merciless touring schedule of clubs he was still too young to drink in. “For the first five years,” he says, “I was on the road non-stop.”

But that old-school apprenticeship sharpened both his chops and songcraft to a razor’s edge. Following up the aforementioned Ledbetter Heights, Shepherd changed his world forever with 1997’s Trouble Is…, the breakthrough second album that saw him write songs of such eye-opening maturity as Blue On Black, and sell over one million copies in an era when post-grunge supposedly held sway. “It was vindication,” he nods.

Shepherd’s studio releases kept gathering pace, from 1999’s Live On to 2004’s The Place You’re In, before 2007’s two time Grammy-nominated album/documentary Ten Days Out: Blues From The Backroads saw him stand up and be counted alongside such giants as B.B. King, Hubert Sumlin and Pinetop Perkins. “I always felt like I owed it to those people to mention their names and the impact they had on me,” he says, “because otherwise you’re doing them a disservice.”

In 2013 and 2016, he even found the bandwidth for two albums with blues-rock supergroup The Rides, also featuring Stephen Stills and Barry Goldberg. But to understand the direction of travel on Dirt On My Diamonds, it pays to revisit 2017’s Lay It On Down, on which Shepherd’s enduring partnership with producer Marshall Altman began. “After Lay It On Down and The Traveler, this is my third consecutive album working with Marshall, and the evolution almost feels like chapters in a book. To me, this album sounds incredibly fresh, modern and current.”

It all started with the aforementioned session at FAME, where Shepherd and his favorite co-writers threw out the rulebook. “Nothing was off-limits,” says the bandleader of penning the songs whose vocal parts would be split down the line between himself and co-vocalist Noah Hunt. “We just wrote non-stop for three days, throwing out songs and letting the good stuff rise to the top. Sometimes with these writing sessions, especially in towns like Nashville, people will set up an appointment, like, ‘OK, we’ll get together from one til three’. But this time, we weren’t under the gun, it was just a bunch of guys having fun writing music. And of course, you feel the history down there in Muscle Shoals. You feel it in the air at a studio like FAME.”

When it came to tracking, the bulk of the sessions went down at the Band House Studios in Los Angeles, with the lineup completed by Chris Layton (drums), Kevin McCormick (bass) and Jimmy McGorman (keys). “It was a really cool, intimate, old-school studio with analogue everything, but it’s since been torn down to make way for a high-rise condo,” sighs Shepherd.

Rolling with the punches, the project recommenced at a friend’s studio in Burbank for the handful of brass, vocal and guitar overdubs. “But the least amount necessary,” stresses the bandleader. “For me, it’s all about capturing the essence of the band playing live together, because that’s what we do best.”

With material this strong, no polish was needed. As on any KWS album, songs are the currency, and the seven originals from Dirt On My Diamonds Volume 1 demand to be heard, lifting listeners above their circumstances at a time when life often feels bleak and bone-raw. “I didn’t want this record to be dark or dreary,” considers Shepherd. “There’s not a lot of incredibly heart-wrenching or difficult subject matter. You know, there’s one blues song called Ease My Mind which is a little dark, about that blues-suffering experience. You Can’t Love Me is about a guy that loves a girl with some unresolved issues. But even that has this really positive sound to it. My goal is always to make music that makes people feel good, regardless of what it’s about.”

For a hit of pure escapism, start with the opening title track: a dynamic barnburner reminding us that sometimes the warts in life are the best part. “Marshall felt particularly passionate that we open with that,” reflects Shepherd. “It’s got the high energy, the rocking guitar, the heavy blues influence – but it sounds incredibly modern at the same time. As for the lyric, it’s about how social media has created this unrealistic expectation, showing everybody how perfect our lives are, when a lot of it is just a façade, y’know?”

While Shepherd has spread the word of the blues founding fathers from the start, the modern sound of highlights like Sweet & Low and Best Of Times speaks to an artist with his antennae up. “When it comes to the lyrics, Sweet & Low is an old-fashioned courting ritual, a guy pursuing a girl,” he explains. “But really that song is about the groove and making people want to get down. There’s the urban influence, the blues influence, the rock influence, but it all comes together and gets people’s attention right off the bat. People I’ve played the album for, they consistently have the biggest reaction to that one.”

“To me,” he continues, “Best Of Times is an observation of the modern-day blues experience. We recently played a show in a really rough, depressed part of the country, but you could tell the community was all in it together, and Marshall and I wrote that song as a result of going through town. Y’know, ‘Grandma standing in the welfare line/Mom and Dad working overtime/bills to pay, mouths to feed…’”

As for the guitar community that follows Shepherd’s every move, the fire and soul across this tracklisting should more than satisfy. “I really like the lead guitar tone from Man On A Mission,” he says. “Then there’s Bad Intentions. I guess that song is like Muddy Waters’ I’m A Man, the guy pounding on his chest, talking about how badass he is. So the guitar tone is really ripping and aggressive, right on the edge, with a lot of hair. I mostly used my favorite ’61 Strat, but when I go in the studio, I have no idea what I’m gonna play – and I just play whatever happens.”

And finally, as befitted this most playful of album sessions, Shepherd dipped into his mental jukebox for a rabble-rousing cover of Elton John’s Saturday Night’s Alright For Fighting. “I always keep a catalogue in the back of my mind of songs I think my band could bring our thing to. The timing worked out well because Elton is doing his farewell tour. Also, I love his guitar player, Davey Johnstone. He’s a friend, too, and when we recorded that song, I sent him a message saying, ‘Hey man, we’re gonna cover Saturday Night’s Alright For Fighting – I hope I don’t screw up your guitar parts’. I almost asked Davey to come into the studio and play it, so that I knew it was 100 per cent correct!”

But then, as he says, perfection is overrated. At a time when mainstream music is polished, quantized and airbrushed of soul, Dirt On My Diamonds sees Kenny Wayne Shepherd catch eight shards of honest human emotion and serve them up raw for an audience that needs real music more than ever. “I just feel a responsibility to make the best music I can make,” he concludes. “And I’m really excited to see what’s gonna happen with these songs when we take them out on the road…”